Since originally created, the USDA Hardiness Zone Map has been revised a total of six times. A planting guide of sorts, the map divides North America into 13 zones governed by average annual extreme minimum winter temperatures and other factors. This map has required some changes over the years due to variations in climate patterns as it continues to change. In pursuit of those goalposts, years later I can now explore how USDA Hardiness Zones have changed over time — and uncover in this process how that has led to more nuanced considerations.

The USDA Hardiness Zone Map

The USDA Hardiness Zone Map originated in 1960 by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). This first map was produced from the average annual minimum temperature measurements for 1948-1957. Gardeners and farmers could then use the map to know which plants were best for planting in their area. The zones were established in 10-degree increments, from Zone 1 to Zone 11; for example, there is a big difference between the warmest end of Borderline and Natives/Warm-Temperate.

1. First Major Revision

The first major revision to the map came in 1965, when another decade of temperature data was added. That updated to a better climatology for the United States as well. But significant advancements were not made until the rise of better computing and data collection technologies in the 1990s.

2. Early Revisions and Technological Advancements

The USDA updated the Hardiness Zone Map again in 1990 using data from different stations that for some areas go back only to 1974 or as early as until at least 1986. This change also brought in half-zone designations, such as Zone 7a and Zone 7b, to further dissect regional climates. The rising amount of observations on detailed meteorological measurements, and better computational methodologies have permitted a more precise mapping the changes im temperature.

3. The Powerful Invisible Hand That Is Climate Change

The most important changes in the USDA Hardiness Zones have been observed as a result of climate evolution. These zone classifications are based on a 30-year average of extreme minimum winter temperatures, so many zones have changed to cooler ones. This has caused many regions to change in their hardiness zones up over the last number of decades. The USDA issued the last update to its Hardiness Zone Map in 2012, drawing on temperature figures for a period of 1976 through years ending. This update revealed a pronounced northward movement of many zones, in line with the observed warming trends over previous decades. In fact, portions of the Midwest and Northeast that once were classified as Zone 5 now fell into Zone 6. Likewise, the southeastern areas moved Zone 7 to Zone 8.

Regional Changes and Their Implication

The changes in USDA Hardiness Zones have been quite different, depending on the region of the United States. Here we examine some of these regional shifts in a little more detail and their impacts on agriculture/horticulture.

1. Northeast

The Northeast was particularly hit by climate change with many areas becoming moving up from Zone 5 to Zone 6. This has broadened the palette of plants that we can grow here – from selected berries to veggies and ornamentals. The downside has been that it makes pests and diseases, many of which do well in a warmer climate.

2. Midwest

In the Midwest, changing from Zone 4 to Zone 5 and in some places going from zoning on into zone has had a large impact on agriculture. Drought-tolerant biofuel crops have enabled farmers to expand other crop production-planting varieties that were formerly off-limits because of the cold winters. But the warmer conditions also have altered where and when precipitation happens, impacting soil moisture and predisposing some regions to more extreme weather.

3. The Southeast

The southeast has experienced a shift from Zone 7 to Parts of zone 8 and in some coastal regions where it previously was listed as being all the way too (zone9). It has broadened the growing time therefore more chances for cultivation of subtropical crops. But it has additionally extended the danger of attacking species and upset normal cycles-like blossoming and natural product developing-which can influence nearby ecosystems.

4. The West

In the western US, hardiness zone migratin has been a result of both temperature and precipitation changes. Zones have shifted to warmer zones particularly in coastal area but shown more variability if further inland. The changes could have major implications for water resources in the dry West, where higher temperatures can raise rates of evaporation and reduce snowpack levels that farmers depend on to deliver water during irrigation.

Future of USDA Hardiness Zones

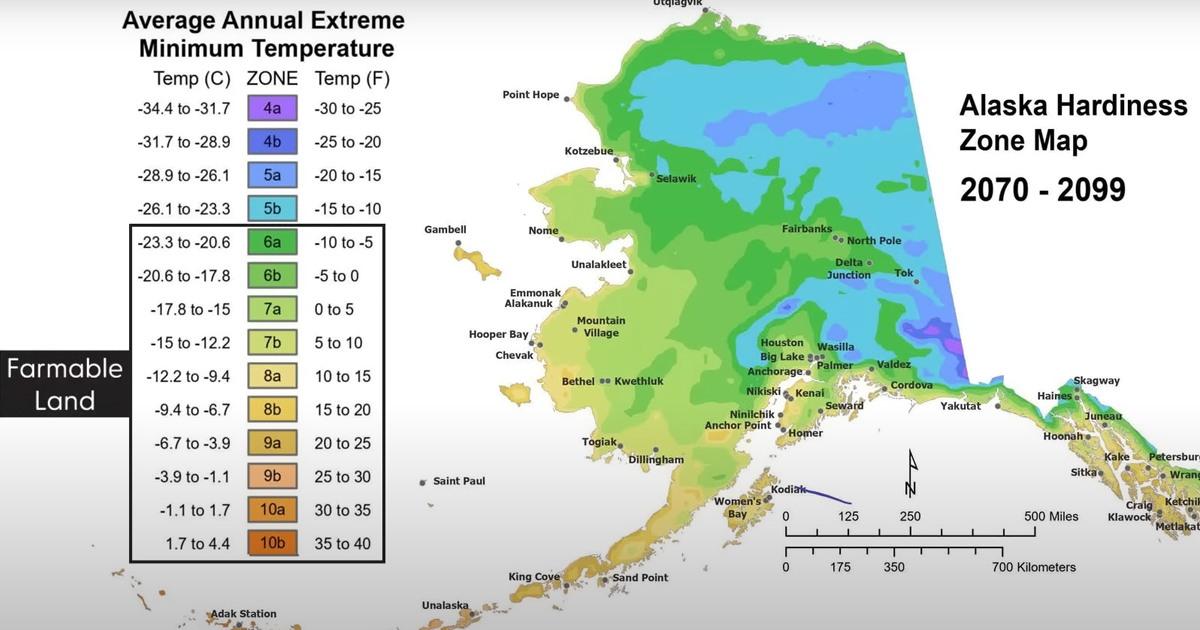

Considering the ongoing march of climate change, it seems plausible that there will be more revisions to the U.S. climatic map at certain points (5). Some predictive models suggest that many areas experiencing warming will remain warm, causing further migrations of the zones. These changes have profound implications for agriculture, horticulture and the natural ecosystems. Farmer Gardeners and land manager receptors will need to sow varieties of pesticides better suited for warmer weather. This could mean trying out different types of crops, changing seasons for planting or harvesting and using some land conservation practices. Furthermore, researchers and policy makers need to work on plans with respect to adjusting the agriculture sector for adapting against climate change along biodiversity.

1. Technology Advances

The question of why hardiness zones are shifting is incomplete without addressing the role advances in technology will play in helping us comprehend and respond to these changes. Better suited climate models, remote sensing technologies and data analytics will provide better temperature and precipitation patterns. By using this information, decision-making can be facilitated and more resilient agricultural systems developed.

Summary

The USDA Hardiness Zone Map is an important resource when learning about the environmental conditions that can impact plant life. Climate change has indeed necessitated revisions to some of these maps over the years; this old park density version likely reflects a warmer era. The shifts in hardiness zones have had profound impacts on agriculture, horticulture and natural ecosystems; requiring non-politicized adaptation measures to new norms. Moving forward, it is paramount we monitor and adjust as our climate changes Through this knowledge of adaption to these shifts, we can protect our agricultural system and conserve biodiversity while maintaining the health productivity of natural environments.